DMM a local climbing hardware manufacturer recently published an article I wrote about my electric campervan. Read the original article on DMM's website here.

Growing up in Snowdonia North Wales DMM has always been one of the local companies I admire the most: their ethos of in-house designing and manufacturing state-of-the-art climbing hardware resonate with me. The DMM factory being located on the shore of Llyn Padarn a leisurely 5min bike ride of my house. 10 years ago when I started my own company I was keen to where possible manufacture locally to keep transportation energy to a minimum. This is worked out well, we still manufacture all our electronic energy monitoring and EV charging hardware in a factory in Bangor, local manufacture has lots of benefits.

It was an honour to write an article for DMM. The reception of the article was very positive, hopefully it will help inspire others to lower the ecological impact of travel. Here is a copy of the article:

Do Climbers Dream of Electric Vans?

Travel is an intrinsic part of climbing. Weekend trips and swapping the winter gloom for Spanish sun is all part of the mix. Climbers enjoy visiting new areas and experiencing different cultures further afield. Glyn Hudson, based in north Wales, has been on a mission to reduce his carbon footprint, and that includes getting to and from the crag.

Walking down from the crag I look forward to our first proper evening in the van. We’d enjoyed good climbing conditions at Dunkeld, with great views of Scottish wild forest and rolling hills, but now the sun has set and the air temperature is falling, I can feel winter is coming. Pulling out my phone I remotely turn on the van heating. I must admit this is one of the luxurious perks of having a fully electric van. Converting our van had been a two month all consuming project. After many evenings sacrificed to wiring, sawing, felting and fabrication it felt great to be finally on a climbing trip and reaping the benefits of all the hard work.

The van doesn’t look out of place in the popular forest car park. It is a non-assuming white Nissan e-NV200, exactly the same size and style as its estranged diesel brother the Nissan NV200. The only really noticeable difference is the charging flap on the front that covers the ports where we plug it in to charge the battery. On the move though, it does sound different. Without an engine electric vehicles are refreshingly quiet; just the sound of the tyres on the road surface and wind noise at higher speeds. Arriving late the night before we had been thankful to be able to stealthily manoeuvre into a free flat spot, without feeling guilty about disturbing the other van dwellers and forest creatures.

Finally, reclined in my swivel seat, a chilled beer from the fridge in hand, layers stripped off in a pleasant 20 degree preheated van I can reflect on what has led us here. As climbers who enjoy the outdoors, I think we all have an affinity with the natural world and care deeply about its conservation, so we and future generations can continue to enjoy it. I’m not going to discuss climate change at length, only to say that David Attenborough recently gave a keynote speech at a climate talk to say that we’re facing “our greatest threat in thousands of years… if we don't take action, the collapse of our civilisations and the extinction of much of the natural world is on the horizon… time is running out"[1]. We need to start making big changes now.

However, there is reason to be positive. The 2018 IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report states that it’s still possible for us to keep global sea level rise under 1.5 deg C, avoiding most of the catastrophic climate effects, if we can reduce carbon emissions by 45% by 2030 [13]. The report goes on to say this reduction is totally possible with the technology available today. I find this very exciting as we have the tools we need to make the required changes without having to live in a cave.

Transport is one of Europe’s biggest sources of CO2 emissions, responsible for over a quarter of all greenhouse gases [2]. So this is a major area where change is needed. Nothing can beat walking, cycling or taking an electric train, but if you want the flexibility of a personal vehicle for transport then electric vehicles (EVs) are currently the lowest carbon option. It goes without saying that flying should be avoided as it emits the most emissions per mile compared to other forms of transportation.

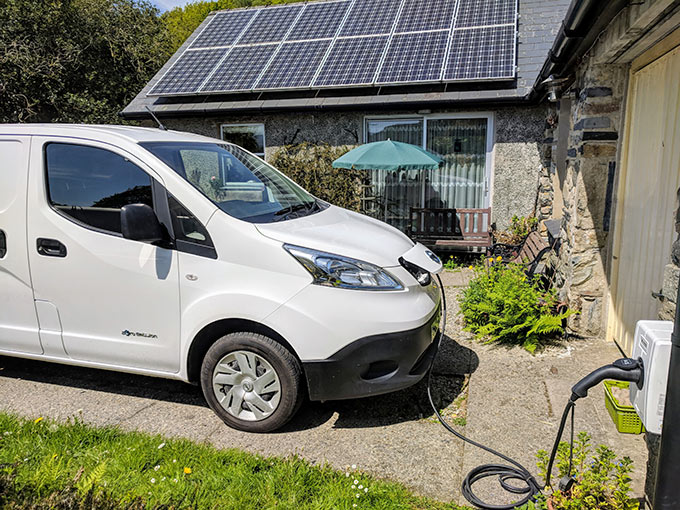

Electricity to power EVs can be 100% renewably generated from solar and wind, and therefore an EV has the potential to be 100% zero carbon to run. Due to the efficiency of electric motors they are also 3x more efficient than internal combustion engines (ICE), so even if they are charged from electricity generated by non-renewable energy, they are still lower carbon than an ICE. Put simply, if you had two cans of diesel, used one in a diesel generator to charge up an EV (not that I would recommend this!) and used the other to fill up an ICE, the EV would travel further[4]. Happily though, a diesel generator is not a current reflection of the UK grid. In 2018 on average, renewable energy provided about 30% of the UK grid, and sometimes over 50%. In Scotland, renewable energy (mainly from wind) produced over 100% of Scotland’s electrical energy demand in November 2018 [3]. At home we charge the van from our solar PV and a green electricity provider.

It is even true that EVs are still the lower carbon option when you take into account the embodied energy required to create the battery. Unlike diesel or petrol, which can only be burnt once, EV batteries can be repurposed for energy storage solutions, and then finally at end-of-life the lithium and cobalt can be recycled [9]. Over its lifetime, taking into account production, an EV will emit 6x less CO2 than a comparable ICE car [14].

A separate but equally compelling argument for EVs is that they have zero tailpipe emissions. Having enjoyed breathing in the fresh forest air earlier today, I’m now painfully aware of a diesel car idling nearby. Many areas of the UK regularly have illegal poor air quality levels which is linked to serious health issues.

Back to more immediate concerns, dinner. We have kitted the van out with an induction hob, a mini fridge and a 12v thermos kettle we can use to boil water. The kettle takes about 10 mins to boil, but with a bit of forethought with switching on, it can be ready to make cups of tea or an AeroPress coffee as soon as you stop at your destination (or on the move if you have an obliging passenger). It’s also handy for making pasta (on the menu tonight) and washing up. With a huge battery already on-board we didn't have to worry about installing a leisure battery.

We can even keep the van’s heating on all night with only a moderate impact on range. If plugged into a campsite hook-up or EV charge point we wake up the following morning fully charged. However, since on this occasion we’re ‘wild’ van camping, we can swing by a nearby EV ‘rapid charger’ to top-up before starting the drive back to Llanberis. It takes 20 mins to top up the van’s battery to 80% and in this instance will cost us nothing because EV chargers are currently free in Scotland and powered by low carbon renewable energy.

So all good in theory but are they practical?

How far will they go? Our van is a second hand 2015 model with a 24kWh battery with 57,000 miles on the clock and is still showing 100% battery capacity. We get 60-80 miles of range, depending on temperature, weather conditions and our driving style.

We travelled home from Scotland to Llanberis (approx 400 miles) with 7x 20min-30min stops in motorway services. With a coffee addiction and an overly excited spaniel who loves his exercise, this is something that actually works fine for us. It is a more leisurely way of travelling, though we would probably have stopped at least 3-4 times in my old diesel van anyway.

Admittedly, our 2015 EV is not suited for all e.g the keen Londoner who wants to leave late on Friday to be in Scotland ready for a Scottish winter alpine day on Saturday. However, the technology for these use cases is already here; the new version of our van with a 40kWh battery can do 100-150 miles and new EV cars such as the Hyundai Kona, Kia e-Niro, Renault Zoe and and Tesla Model 3 have 200-300 miles of range, considerably more than most people’s bladder range! Like most people we only make these longer journeys a handful of times per year. Day-to-day around home in north Wales: going to work, climbing in the Pass, Orme or the local indoor wall the range of our van is more than sufficient to never have to worry about it.

How much do they cost?

While EVs currently have a higher upfront cost, this is made up for by the very low running and maintenance costs. Public chargers are currently free in Scotland and charging from home will cost around 1.5p - 3p per mile. A full charge of our van costs us £1-£2 of electricity if charged overnight with an off-peak tariff [6]. The trip to Scotland (800 mile round journey) cost less than £20. The same trip in my old diesel van would have cost approx £140. EVs are also tax free and need hardly any maintenance. There is no engine oil to change or clutch, gearbox, turbo, exhaust... to replace. In swapping my partner’s diesel Citroen C3 car to an electric Nissan LEAF, and then my diesel Citroen Dispatch van to the e-NV200, we worked out that on average an EV will save us around £1000/yr compared to an ICE car, or £2000/yr compared to an ICE van, therefore saving us £3000/yr in total.

We paid £9500 (inc. VAT) for our 2nd hand 3-year old Nissan e-NV200 with 30k miles and did a DIY campervan conversion. There’s no doubt that the high up front cost of an EV is a big hit, however since the overall lifetime cost of ownership will be lower than an equivalent ICE vehicle, EVs are more of a financing issue rather than an affordability issue. Leasing, contract purchase, loan and/or 2nd hand purchase are all options.

All EVs come with an 8yr or 100,0000 miles battery warranty and there are many real-world examples of EV batteries achieving double this mileage [10][11].

How and where can you charge? We charge the van overnight at home. Plugging the van in every couple of days cumulatively takes less time than filling up with diesel once per month, actually saving me time [5]. If charging at home was not possible a newer EV with larger battery would only need to be charged once per week which could be done at work or while doing the weekly shop.

The UK already has a decent (and rapidly expanding) EV charging network. Using the public charging network can seem daunting at first but there are good apps out there such as PlugShare.com and Zapmap.co.uk which map them all out and assist you in planning a long journey. As the network includes different providers, having to download multiple apps and sign up to various sites is a bit of a pain. However, most rapid EV charging stations are now moving over to using contactless card payments, just like a petrol pump.

Can we get to all the crags?

So far in 3 years of EV driving we have clocked up 73,000 fully electric miles and have never yet to run out of electrons. We’ve been on multiple trips to NW Scotland [12], London, Paris (Font) [7], and even Ceuse in the French Alps [8]. We’re currently looking forward to taking our EV campervan on a climbing trip to southern Spain and the Austrian Alps later this summer. (has this passed? i.e. was it summer 2018? GLYN: it was summer 2019, I’ve added an update below)

Update: Since writing this article Glyn and his partner Amy, and their dog Bailey, have successfully taken their electric van to Hungary (via the Austrian alps and Osp in Slovenia), Jaén and Chulilla in Spain and Seynes in France.

Bio

Glyn Hudson runs an energy monitoring company, OpenEnergyMonitor and is an enthusiastic advocate of living within our ecological limits. A keen climber for 17 years, he attempts to live-by his sustainability principles. This includes climbing trips further afield, avoiding flying. Previously, Glyn has used trains to reach climbing destinations in France, Spain, Italy, Norway, Morocco, Greece, Turkey and China. Glyn keeps a blog of his adventures at https://zerocarbonadventures.co.uk.

For more information on the van conversion see Glyn's blog post: Nissan e-NV200 campervan conversion.

References

[1] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/amp/science-environment-46398057.

[2] https://www.transportenvironment.org/sites/te/files/publications/2018_04_CO2_emissions_cars_The_facts_report_final_0_0.pdf

[3] https://twitter.com/HomeEnergyScot/status/1072770564681551872?s=19

[4] https://insideevs.com/tesla-model-s-charged-by-diesel-generator-cleaner-than-ice-wvideo/

[5] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TWCtB5qaX4c&t=547s

[6] https://www.octopusev.com/octopus-go

[7] https://blog.zerocarbonadventures.co.uk/2017/12/north-wales-to-fontainebleau-via.html

[8] https://blog.zerocarbonadventures.co.uk/2017/07/ceuse-2017-nwales-to-french-alps-in.html

[9] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rdqtFXyDLIo

[10]https://www.facebook.com/candctaxis/posts/the-2nd-100-electric-nissan-leaf-we-added-to-our-fleet-is-affectionately-named-w/1863314977272516/

[11] https://insideevs.com/highest-mileage-tesla-now-has-over-420000-miles/

[12] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-cVlfmcwlAg

[13] https://report.ipcc.ch/sr15/pdf/sr15_spm_final.pdf

[14] https://twitter.com/AukeHoekstra/status/1083705012080074753

Travel is an intrinsic part of climbing. Weekend trips and swapping the winter gloom for Spanish sun is all part of the mix. Climbers enjoy visiting new areas and experiencing different cultures further afield. Glyn Hudson, based in north Wales, has been on a mission to reduce his carbon footprint, and that includes getting to and from the crag.

Walking down from the crag I look forward to our first proper evening in the van. We’d enjoyed good climbing conditions at Dunkeld, with great views of Scottish wild forest and rolling hills, but now the sun has set and the air temperature is falling, I can feel winter is coming. Pulling out my phone I remotely turn on the van heating. I must admit this is one of the luxurious perks of having a fully electric van. Converting our van had been a two month all consuming project. After many evenings sacrificed to wiring, sawing, felting and fabrication it felt great to be finally on a climbing trip and reaping the benefits of all the hard work.

The van doesn’t look out of place in the popular forest car park. It is a non-assuming white Nissan e-NV200, exactly the same size and style as its estranged diesel brother the Nissan NV200. The only really noticeable difference is the charging flap on the front that covers the ports where we plug it in to charge the battery. On the move though, it does sound different. Without an engine electric vehicles are refreshingly quiet; just the sound of the tyres on the road surface and wind noise at higher speeds. Arriving late the night before we had been thankful to be able to stealthily manoeuvre into a free flat spot, without feeling guilty about disturbing the other van dwellers and forest creatures.

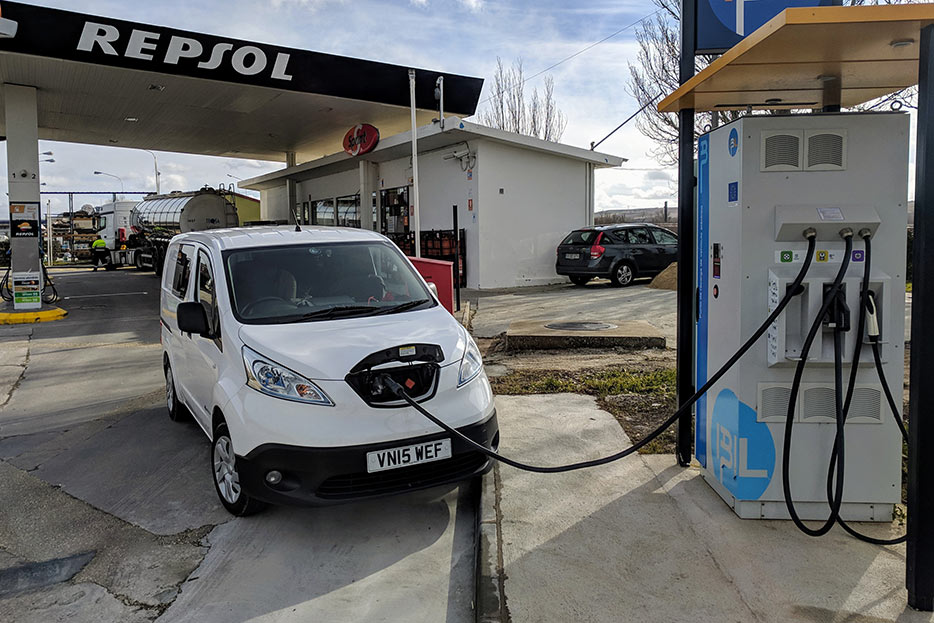

|

| Rapid charging in Spain |

Finally, reclined in my swivel seat, a chilled beer from the fridge in hand, layers stripped off in a pleasant 20 degree preheated van I can reflect on what has led us here. As climbers who enjoy the outdoors, I think we all have an affinity with the natural world and care deeply about its conservation, so we and future generations can continue to enjoy it. I’m not going to discuss climate change at length, only to say that David Attenborough recently gave a keynote speech at a climate talk to say that we’re facing “our greatest threat in thousands of years… if we don't take action, the collapse of our civilisations and the extinction of much of the natural world is on the horizon… time is running out"[1]. We need to start making big changes now.

However, there is reason to be positive. The 2018 IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report states that it’s still possible for us to keep global sea level rise under 1.5 deg C, avoiding most of the catastrophic climate effects, if we can reduce carbon emissions by 45% by 2030 [13]. The report goes on to say this reduction is totally possible with the technology available today. I find this very exciting as we have the tools we need to make the required changes without having to live in a cave.

Transport is one of Europe’s biggest sources of CO2 emissions, responsible for over a quarter of all greenhouse gases [2]. So this is a major area where change is needed. Nothing can beat walking, cycling or taking an electric train, but if you want the flexibility of a personal vehicle for transport then electric vehicles (EVs) are currently the lowest carbon option. It goes without saying that flying should be avoided as it emits the most emissions per mile compared to other forms of transportation.

Electricity to power EVs can be 100% renewably generated from solar and wind, and therefore an EV has the potential to be 100% zero carbon to run. Due to the efficiency of electric motors they are also 3x more efficient than internal combustion engines (ICE), so even if they are charged from electricity generated by non-renewable energy, they are still lower carbon than an ICE. Put simply, if you had two cans of diesel, used one in a diesel generator to charge up an EV (not that I would recommend this!) and used the other to fill up an ICE, the EV would travel further[4]. Happily though, a diesel generator is not a current reflection of the UK grid. In 2018 on average, renewable energy provided about 30% of the UK grid, and sometimes over 50%. In Scotland, renewable energy (mainly from wind) produced over 100% of Scotland’s electrical energy demand in November 2018 [3]. At home we charge the van from our solar PV and a green electricity provider.

It is even true that EVs are still the lower carbon option when you take into account the embodied energy required to create the battery. Unlike diesel or petrol, which can only be burnt once, EV batteries can be repurposed for energy storage solutions, and then finally at end-of-life the lithium and cobalt can be recycled [9]. Over its lifetime, taking into account production, an EV will emit 6x less CO2 than a comparable ICE car [14].

|

| Rental Tesla in Norway |

A separate but equally compelling argument for EVs is that they have zero tailpipe emissions. Having enjoyed breathing in the fresh forest air earlier today, I’m now painfully aware of a diesel car idling nearby. Many areas of the UK regularly have illegal poor air quality levels which is linked to serious health issues.

Back to more immediate concerns, dinner. We have kitted the van out with an induction hob, a mini fridge and a 12v thermos kettle we can use to boil water. The kettle takes about 10 mins to boil, but with a bit of forethought with switching on, it can be ready to make cups of tea or an AeroPress coffee as soon as you stop at your destination (or on the move if you have an obliging passenger). It’s also handy for making pasta (on the menu tonight) and washing up. With a huge battery already on-board we didn't have to worry about installing a leisure battery.

We can even keep the van’s heating on all night with only a moderate impact on range. If plugged into a campsite hook-up or EV charge point we wake up the following morning fully charged. However, since on this occasion we’re ‘wild’ van camping, we can swing by a nearby EV ‘rapid charger’ to top-up before starting the drive back to Llanberis. It takes 20 mins to top up the van’s battery to 80% and in this instance will cost us nothing because EV chargers are currently free in Scotland and powered by low carbon renewable energy.

So all good in theory but are they practical?

How far will they go? Our van is a second hand 2015 model with a 24kWh battery with 57,000 miles on the clock and is still showing 100% battery capacity. We get 60-80 miles of range, depending on temperature, weather conditions and our driving style.

We travelled home from Scotland to Llanberis (approx 400 miles) with 7x 20min-30min stops in motorway services. With a coffee addiction and an overly excited spaniel who loves his exercise, this is something that actually works fine for us. It is a more leisurely way of travelling, though we would probably have stopped at least 3-4 times in my old diesel van anyway.

Admittedly, our 2015 EV is not suited for all e.g the keen Londoner who wants to leave late on Friday to be in Scotland ready for a Scottish winter alpine day on Saturday. However, the technology for these use cases is already here; the new version of our van with a 40kWh battery can do 100-150 miles and new EV cars such as the Hyundai Kona, Kia e-Niro, Renault Zoe and and Tesla Model 3 have 200-300 miles of range, considerably more than most people’s bladder range! Like most people we only make these longer journeys a handful of times per year. Day-to-day around home in north Wales: going to work, climbing in the Pass, Orme or the local indoor wall the range of our van is more than sufficient to never have to worry about it.

How much do they cost?

While EVs currently have a higher upfront cost, this is made up for by the very low running and maintenance costs. Public chargers are currently free in Scotland and charging from home will cost around 1.5p - 3p per mile. A full charge of our van costs us £1-£2 of electricity if charged overnight with an off-peak tariff [6]. The trip to Scotland (800 mile round journey) cost less than £20. The same trip in my old diesel van would have cost approx £140. EVs are also tax free and need hardly any maintenance. There is no engine oil to change or clutch, gearbox, turbo, exhaust... to replace. In swapping my partner’s diesel Citroen C3 car to an electric Nissan LEAF, and then my diesel Citroen Dispatch van to the e-NV200, we worked out that on average an EV will save us around £1000/yr compared to an ICE car, or £2000/yr compared to an ICE van, therefore saving us £3000/yr in total.

We paid £9500 (inc. VAT) for our 2nd hand 3-year old Nissan e-NV200 with 30k miles and did a DIY campervan conversion. There’s no doubt that the high up front cost of an EV is a big hit, however since the overall lifetime cost of ownership will be lower than an equivalent ICE vehicle, EVs are more of a financing issue rather than an affordability issue. Leasing, contract purchase, loan and/or 2nd hand purchase are all options.

All EVs come with an 8yr or 100,0000 miles battery warranty and there are many real-world examples of EV batteries achieving double this mileage [10][11].

How and where can you charge? We charge the van overnight at home. Plugging the van in every couple of days cumulatively takes less time than filling up with diesel once per month, actually saving me time [5]. If charging at home was not possible a newer EV with larger battery would only need to be charged once per week which could be done at work or while doing the weekly shop.

The UK already has a decent (and rapidly expanding) EV charging network. Using the public charging network can seem daunting at first but there are good apps out there such as PlugShare.com and Zapmap.co.uk which map them all out and assist you in planning a long journey. As the network includes different providers, having to download multiple apps and sign up to various sites is a bit of a pain. However, most rapid EV charging stations are now moving over to using contactless card payments, just like a petrol pump.

Can we get to all the crags?

So far in 3 years of EV driving we have clocked up 73,000 fully electric miles and have never yet to run out of electrons. We’ve been on multiple trips to NW Scotland [12], London, Paris (Font) [7], and even Ceuse in the French Alps [8]. We’re currently looking forward to taking our EV campervan on a climbing trip to southern Spain and the Austrian Alps later this summer. (has this passed? i.e. was it summer 2018? GLYN: it was summer 2019, I’ve added an update below)

Update: Since writing this article Glyn and his partner Amy, and their dog Bailey, have successfully taken their electric van to Hungary (via the Austrian alps and Osp in Slovenia), Jaén and Chulilla in Spain and Seynes in France.

Bio

Glyn Hudson runs an energy monitoring company, OpenEnergyMonitor and is an enthusiastic advocate of living within our ecological limits. A keen climber for 17 years, he attempts to live-by his sustainability principles. This includes climbing trips further afield, avoiding flying. Previously, Glyn has used trains to reach climbing destinations in France, Spain, Italy, Norway, Morocco, Greece, Turkey and China. Glyn keeps a blog of his adventures at https://zerocarbonadventures.co.uk.

For more information on the van conversion see Glyn's blog post: Nissan e-NV200 campervan conversion.

References

[1] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/amp/science-environment-46398057.

[2] https://www.transportenvironment.org/sites/te/files/publications/2018_04_CO2_emissions_cars_The_facts_report_final_0_0.pdf

[3] https://twitter.com/HomeEnergyScot/status/1072770564681551872?s=19

[4] https://insideevs.com/tesla-model-s-charged-by-diesel-generator-cleaner-than-ice-wvideo/

[5] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TWCtB5qaX4c&t=547s

[6] https://www.octopusev.com/octopus-go

[7] https://blog.zerocarbonadventures.co.uk/2017/12/north-wales-to-fontainebleau-via.html

[8] https://blog.zerocarbonadventures.co.uk/2017/07/ceuse-2017-nwales-to-french-alps-in.html

[9] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rdqtFXyDLIo

[10]https://www.facebook.com/candctaxis/posts/the-2nd-100-electric-nissan-leaf-we-added-to-our-fleet-is-affectionately-named-w/1863314977272516/

[11] https://insideevs.com/highest-mileage-tesla-now-has-over-420000-miles/

[12] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-cVlfmcwlAg

[13] https://report.ipcc.ch/sr15/pdf/sr15_spm_final.pdf

[14] https://twitter.com/AukeHoekstra/status/1083705012080074753

.png?lang=en-GB)